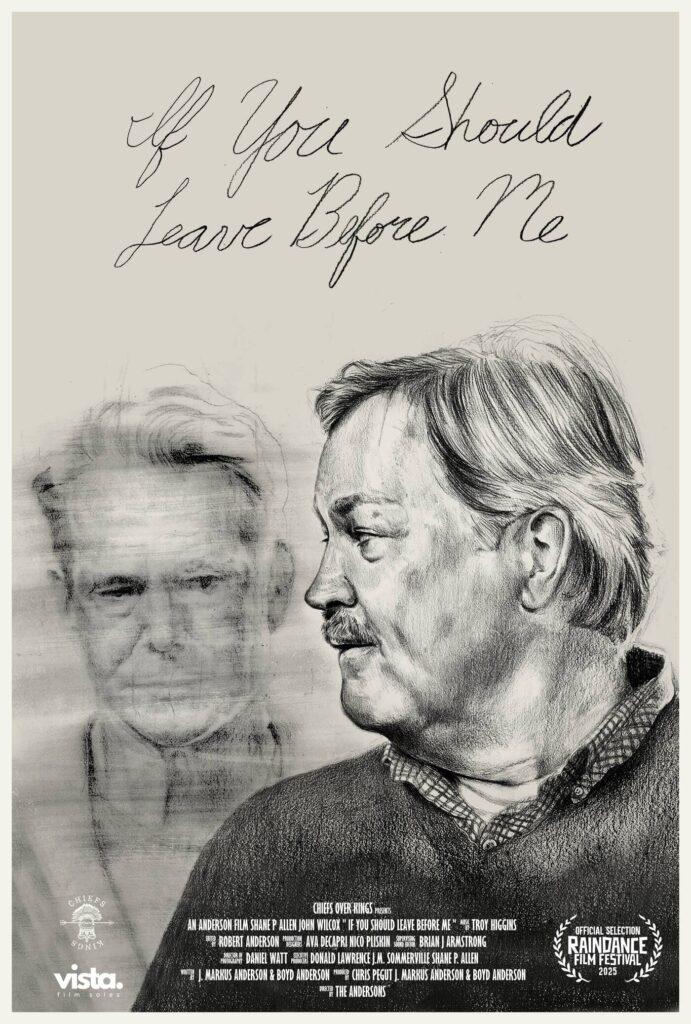

Premiering at the 2025 Raindance Film Festival, it’s a heartfelt meditation on grief, hope, and the beauty of moving forward. We spoke with the Andersons about turning personal pain into art, building entire worlds from scratch, and why humor and heartbreak often share the same space.

If You Should Leave Before Me explores love, grief, and the afterlife in such an original way. What first sparked the idea for this story, and how did it evolve into the film we see today?

J. Markus Anderson – Writing sessions for us are always such a whirlwind. I honestly have a hard time remembering where an idea originally came from, or who came up with it. I think this is a good thing though, because it means our writing is so congruent with each other that everything really melds together into one solid piece. During COVID, we had so many deaths happen in our family that I think subconsciously the topics of grief and the afterlife just made their way into our story.

Boyd Anderson – We’ve wanted to make movies for as long as I can remember. That’s the reason we moved out to California in the first place. Well, we’d been here for over 12 years and hadn’t made a movie. Sure we made shorts, and web series, but never a movie. We blamed that on not having the time or resources; countless reasons why we couldn’t or hadn’t. Then COVID happened. It was a gift of time. Trapped in doors for months. It was a perfect opportunity to write a movie. Well, we didn’t write then either. We wasted that time. Angry at ourselves, we realised you can’t just wait for things to be perfect to start. If you do that you’ll be waiting forever. So we decided to just go for it. I listened to a lot of interviews and podcasts and heard Taylor Sheridan say he wrote a whole script in one month. I thought that was crazy and we decided to try it, just to get back into writing. Well, at the end of that month, this is the script we had. Like Markus said, it’s all kind of a blur. After we had a blind table read and people cried, we knew we had something good. Something worth making.

You’ve spoken about the film being a form of therapy after personal loss. How did making this project help you process those experiences, and was there ever a moment it felt too close to home?

J. Markus – In the middle of the shoot we lost our grandmother, our mom’s mother. When making a movie, your whole life becomes consumed by its story. This being about death and grief brought up a lot of memories from the ones we had lost. But then to actually have someone pass away was really intense. And because we were a very small, independent film, we weren’t able to leave the production, which left me with this regret of feeling like I was abandoning my family. Luckily, the services were moved a few weeks later until we were done filming and we were able to attend.

Boyd – That was rough. I remember it was right before we filmed the tub girl scene, which is the most emotional scene in the movie. Maybe that fueled that scene more? I don’t know. A lot of these things I’m realizing after the fact. Like, our father passed away right before I was born. Markus was 4. He passed away in the house we grew up in, on the couch from cancer. I think that’s why Joshua is sick in the living room. I think hearing all those stories, and Markus being so young when that happened, ended up in the script in this way.

The film features surreal, imaginative realms like “cardboard world” and the antique-filled plate house. How did you design and build these sets while working within an indie budget?

Boyd – We come from a construction background so being able to build these worlds on our own, with the help from our cousin Jake, was a way we knew we could save money. Cardboard world was the only set where we needed help. So we collaborated with Nico and Ava (Art Department) to help bring this world to life. Ava designed multiple color options and patterns for the world beforehand so we could choose which would work best. The first version they brought to us was very realistic looking. But as impressive as it was, we wanted this first world to feel more child-like. As if 4th graders made it for a class play. We knew this world was going to be the first one we saw on screen and we needed it to feel larger in scope than the rest. They spent a long time building dozens if not hundreds of trees and clouds and even large cardboard mountains for the background.

Everyone was very nervous about shooting cardboard world. I remember Dan, our cinematographer, saying “I’ve never lit a cardboard world before”. In the end, it worked out just how we imagined.

J. Markus – As for the rest of the sets, about 6 months prior to production, once we thought, “Ok we are going to do this film” we started grabbing everything for free that we could on Craigslist. Estate sales, garage sales, etc. We just stuffed a storage unit full of anything we could find. One estate sale had the whole living room filled with plates, and they were free! So we grabbed them all. At that point we really hoped the film wouldn’t fall through or else we would be stuck with all this junk. Our construction knowledge was a huge asset. We were able to save so much money building everything ourselves. And we were able to pull off things that people were telling us we couldn’t do, like the floor raising. That was one of those moments where we argued about whether it was worth the cost of purchasing a hydraulic lift, arguably the most expensive item we bought. Once you see the film, I think the shots we got were worth it.

What inspired the decision to use practical, handmade environments instead of leaning on CGI?

J. Markus – We love the tangible, real, and the practical. Some of it came from us having no idea how to work with CGI. We had very small moments – wire removal, some very minor set extensions. In cardboard world, there was a part of the warehouse ceiling that you could see, and they went in and just covered it digitally with blue paper. For me, some of the most exciting parts of making a film is walking onto a magical set. I don’t act, but I can imagine walking onto a set for the first time has to help sell the character. I think some filmmakers have just gotten so used to “fixing it in post” and I feel you lose a sense of true authorship that way. I like being forced into a decision, something finite. Isn’t that what life is?

Boyd – It’s just what we know. We have all the tools. We have the saws and welders and what not, so building seemed easier to us. And like Markus said, how cool is it for the actors to be able to interact within these real worlds. I remember when the stunt coordinator came in for the fight scene he asked, “What can we break?” We said, “Everything!” He was used to being on sets where people had to return items that the production had rented. We needed to break as many things as possible so that floor raising would work better.

Grief can be a heavy subject, but your film mixes it with humor, fantasy, and even pop culture references. How did you strike the right tonal balance?

J. Markus – From the script phase, we knew that a fine balance of humor with the heavy emotions would actually amplify both. An audience can only sit with sadness for so long before they become catatonic to your story. The humor pulls them back out so we can hit them again with it. (Laughs) One of my favorite scenes was actually cut. The dinner scene with Plate Lady had another five minutes and it was hilarious, but it didn’t serve the tone correctly.

Boyd – This is a question that when we first made the movie, I wouldn’t get. I didn’t feel like the tone shifting was a crazy idea. Or that using memes and what not was risky. I think we just made what we wanted. We didn’t really think about how an audience would react. We knew we both liked it and just went for it. Now that it is done and we’ve watched it with live audiences around the world, I get how some of these things could have not landed and maybe ruined the whole film. There’s stuff in the first edit that didn’t work and we had to cut or change. But, I think when you make a movie you can’t be too worried about what others are going to say. Not everyone will like your film, and that’s okay. Just make sure you like it and you’ll find your audience.

Shane P. Allen and John Wilcox carry the emotional weight of the story beautifully. What was your process in finding and working with them to bring Mark and Joshua to life?

J. Markus – The crazy thing is, these two guys were the first people to read these characters. When we finish a script, we like to bring actors out to read it. We do it cold. No one knows anything about the story or the characters. We just simply read it from front to back. We want to see if people can pull out the necessary information just from the script. It’s really a great exercise. Just so happens Shane and John read for their respective characters. We kinda knew at that moment that these were our guys.

Boyd – There was a moment when Shane was going to have to pull out of the movie due to scheduling issues. That was stressful. Their chemistry was perfect. It’s simply too good. There’s another meme for you. I don’t know what this film would look like without them but I’m glad we will never have to know.

The film includes striking visual rules—like Mark always moving right to left. Can you talk about how you developed this cinematic language and why it was important to the storytelling?

Boyd – Daniel Watt, our cinematographer, spent a lot of time with us in preproduction talking about the movie. When the warehouse was still empty the three of us took the script and some tape and planned out the house dimensions to make sure it’d work for each scene before we built it. It was a long process that took many many sessions of walking through the whole script and talking about each scene. I worked with our storyboard artist, Eden, to draw these shots out. At the same time, Dan created the house in Unreal Engine to create his own type of storyboards. I know many other filmmakers like to figure the shots out on the day of shooting because they think it’s limiting to have a strict shot list but I think the opposite is true. You can’t come up with some of these very complicated shots on the day. The sets were built around the shots. This isn’t limiting what we can do, it’s enhancing it. And there are still times when you’re shooting that you find something else that is better or unique, and you can pivot. But you should go into each scene with a strong plan.

J. Markus – As far as the importance for storytelling, I feel like film has such strong established rules, at least in western culture, the fact that we read left-to- right and our heroes are typically shown moving with progress in that same direction. It was really fun to go against that, which was also really difficult. We had these framing rules and sometimes it limited us to only one place for the camera. And obviously we break the rule here and there, but it gave a nice visual motif to the story. The fact that Mark is moving through our frame “backwards” until a certain choice is made.

The afterlife has been imagined in countless films, from What Dreams May Come to Beetlejuice. Were there any particular works that influenced or inspired your vision?

J. Markus – Everything Everywhere All At Once is one we talk about a lot. It really gave us courage to embrace some of the more absurd ideas we have. Terry Gilliam is a big inspiration with his big and bold set designs. Obviously, the films you mentioned. A more surprising inspiration would be Inside Llewyn Davis by The Coens. That film to me is such a melancholy mood, and that’s something that I wanted to carry into this film.

Boyd – This is kind of embarrassing but I haven’t seen a lot of those films. Definitely agree with the Everything Everywhere All At Once. That was probably our best comparison with tone. I remember seeing the 3rd episode of The Last Of Us season 1 and thinking about how nicely that couple reflected ours. If I remember correctly, we had finished writing ours before seeing that episode but hadn’t yet filmed yet. I think I need to watch more films.

Indie filmmaking often requires creative problem-solving. Was there a specific on-set challenge that stands out as especially difficult—or surprisingly rewarding?

Boyd – The doors never really worked how we intended. We had done some test shots for the doors bursting through the wall and those tests worked perfectly but on the days of filming it never worked that way again. The door that appears behind Mark and Joshua before going into Plate Lady world was one of those problems. We had to reset it multiple times, which took a long time. We had to fix the drywall and repaint the wall. On the 3rd take it didn’t break all the way through again. But we kept rolling and Shane and John stayed in character and that’s what ended up in the film.

J. Markus – And when he says we had to fix that wall, he literally means us. It was us two and our cousin, Jake, who is the MVP of this production. We would put the drywall back up, mud it, paint it, put a fan on it to make sure it dried quickly and then run it again. I was the one behind the curtain slamming the door and unfortunately we did some bad measuring so the door was hitting the frame. Making an indie film, you will have something catastrophic happen every single day. But that’s also the fun. We actually get really nervous if the day is almost over and we had no problems. That means there’s a big one happening at the end of the day. So, we actually are thrilled when the day starts with a problem; get it out of the way early. The tile for the kitchen counter I wanted was a very specific tile, and it didn’t arrive until the morning we needed it. So I had someone gluing it down as we ran some of the blocking.

You’ve filled the film with homages, Easter eggs, and even memes. Do you see this playful layer as a way of grounding the surreal story in our modern culture?

J. Markus – Yes and no. The first meme reference was “Daddy Chill” and it happened accidently. When we wrote the scene, the dialogue was really close to it. So as I read it back, the idea kicked into my head so we placed it in. Not knowing if it would work, and then we started to throw some more in, we didn’t want to oversaturate it, but everyone has really been loving the references. We also didn’t want it to look like we were trying to be relevant to modern culture so we chose references that were already ten or so years old. One of our friends says it’s cringe, but I think it works.

Boyd – Yeah, I think we were just crazy enough, or maybe naive enough, to try anything. Which is a good asset. You only get to make your first movie once and it’s the only time you won’t really know what you’re doing. So just go for it and don’t let people tell you what you can and can’t do. Now, the secret is to hold onto that as we make more films with higher budgets.

At its core, the film is about letting go. What do you hope audiences take away emotionally after watching If You Should Leave Before Me?

Boyd – As sad as this film can be at times, I hope audiences leave feeling appreciative of the love and people they have in their lives. And for ones who are struggling with similar things as Mark, I hope this leaves them feeling like there is a light at the end of the tunnel of grief, and that the grief they are feeling is a privilege of experiencing such a love.

J. Markus – Hope. As we’ve been talking about this movie with more and more people, we’ve come to realize it’s not about letting go or moving on, but moving forward.

Finally, as brothers and creative partners, how do you divide roles on set—and what do you think each of you brings that the other doesn’t?

J. Markus – This question comes up a lot. I’ve never really thought about it until now. We really just get along well creatively. We do all our arguing before production, which people, once they work with us, are surprised to hear because on set we really don’t. But it’s because we establish such a solid plan that we both agree on. On set you could ask either of us a question and get the same answer. We also have an unspoken rule that we both can’t be tired or grumpy on the same day. So, if I feel that his energy is down I just instinctively know that I need to step up.

Boyd – We’ve always been like this. Even when we worked construction together. If I was on a job and Markus called and said something was broken and needed a new piece, I wouldn’t second guess it. We trust that the other did everything we would have done. And that has come into play with filmmaking as well. We write over each other words in early stages of writing so there isn’t a “This is my part” and “This is his part it.” There is just the script, and just the movie.