Set during an intimate evening of readings in a Baltimore apartment, the film unfolds as both personal reflection and collective experience. Thomas reads poems written in his early twenties—texts forged during a period of emotional instability, social awakening, and self-discovery—now voiced from the perspective of a man who has lived through multiple careers, cities, and chapters of American life. The distance between who he was and who he is becomes the film’s quiet engine.

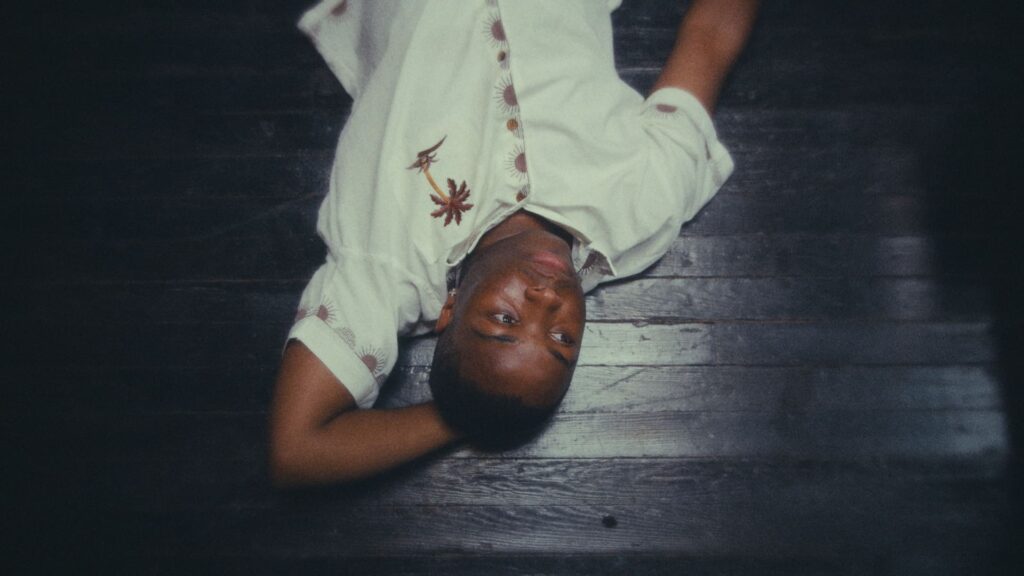

Blending live performance, archival footage, and carefully staged visual interludes, In Need of Seawater expands beyond a poetry reading into what feels like a visual poem—one that traces identity, politics, masculinity, and survival through language. The presence of a younger version of Thomas on screen deepens this dialogue, creating a layered conversation between past and present, mentor and mentee, memory and legacy.

In this interview with IndieWrap, Thomas reflects on returning to his early work, the role poetry played as a form of survival, and how his creative life intersects with decades spent in journalism, public leadership, and economic development. He also discusses the evolution of his voice, the intentions behind the trilogy, and what he hopes younger artists might take from revisiting their own beginnings.

What emerges is not only a conversation about a film, but about time, authorship, and the enduring power of creative expression to anchor a life.

1. In Need of Seawater revisits poems written more than twenty years ago. What was the emotional experience of returning to those words now, as a different man living in a different America?

It was a beautiful and grounding process. The challenges I was wrestling with then, and the hope I believed existed at the end of the tunnel, are now clear to me from the other side. What interested me most was not nostalgia, but translation. I wanted to carry that younger voice forward in a way that resonates with people navigating early adulthood today, regardless of where they live. Across the world, young people are still finding their voices, but the social, economic, and cultural conditions shaping those journeys are very different now.

2. The film treats the past not as nostalgia, but as a map. When you look back at The Poetic Repercussion today, what directions does it still point you toward?

It is still a roadmap, one that is familiar to me but not always to others. Twenty years ago, therapy and deep self-reflection were far more taboo, especially for men. Watching friends, fraternity brothers, and family members come of age over time has reinforced how critical ownership and self-actualization are. Many men struggle to process emotion and pain. The film points toward a few quiet solutions: finding inner strength, leaning on community and legacy, and allowing silence to do some of the work. Those poems still point toward that work.

3. Hearing you read these poems aloud as an adult adds a new layer of meaning. How did time, lived experience, and distance reshape your relationship to the language you wrote in your early twenties?

The language means more to me now than it did then. I am grateful I documented those emotions with such care. The book spans an emotional range I could not write in the same way today. That is the timestamping power of creativity. It captures who you were, honestly, in that moment. I did not want the film to be about the book itself, but about the poems and the journey they represent.

4. The setting of the film, a small, intimate gathering in a private apartment, creates a powerful sense of closeness. Why was it important for this project to unfold in such a personal, almost domestic space?

At their best, poetry readings are intimate. Often there is no microphone, only candlelight, reflective pauses, and an audience there for connection. Director Richard Yeagley first had to capture the performance honestly, then translate that intimacy into a cinematic experience that could hold attention beyond the room itself.

5. The documentary blends poetry readings with archival footage, staged scenes, and memory-like images. How did you and Richard Yeagley decide which moments should remain grounded in reality and which should drift into interpretation?

Creating a beautiful poetic film was the overarching vision, but the goal was always balance. The imagery needed to elevate the words and the performance, not compete with them. That meant a deeply collaborative process—working with Richard and with Ziaire Mann, who portrays a younger version of me, to situate each poem within its emotional and historical context so it could be fully and honestly brought to life.

6. Your poetry often moves fluidly between the deeply personal and the broadly political. In the film, those two dimensions feel inseparable. How do you see your personal story reflecting a larger American narrative?

The film inevitably intersects with my journalism and economic development work. How we show up professionally is shaped by our personal histories. This project reverses that order, telling my personal story against the backdrop of a changing country. Each decade I have lived through left a distinct social imprint, and those experiences are intentionally woven into the reflective voice of a 21-year-old.

7. The presence of a younger version of yourself in the film creates a quiet dialogue across generations. What did that visual conversation mean to you while making the film?

It can be read two ways. As mentor and mentee, or as a conversation with my younger self. Either way, the poetry represents a journey many young people are on, searching for language, grounding, and permission to feel deeply.

8. Much of your life has been spent in leadership roles across journalism, economic development, and public service. How has that world influenced the way you think about art, voice, and responsibility as a poet and filmmaker?

Leadership has sharpened my sense of responsibility around clarity and intention. Art does not exist in a vacuum. It shapes narratives, influences perception, and creates space for empathy. That awareness has made me more disciplined and more committed to using my voice thoughtfully.

9. The film suggests that language was not just expression for you, but survival. Can you talk about a moment in your life when poetry quite literally carried you through uncertainty or upheaval?

In my early twenties, poetry was how I processed instability emotionally, financially, and existentially. Before I had language for therapy or frameworks for self-work, poetry gave me structure. It helped me make sense of chaos when I did not yet have other tools.

10. In Need of Seawater is the first chapter in a poetic documentary trilogy. Without giving too much away, how do you imagine the “present” and “future” chapters will differ emotionally and formally from this one?

The trilogy tracks my transition to Baltimore, one of America’s great cities and a profound artistic hub, and reflects my commitment to becoming part of this community.

This first film is rooted in the past and intentionally blends my youth in Atlanta with Maryland’s artists and filmmaking community. The next chapters will feature poems and creative work I have developed since arriving. I am taking my time. I have a demanding career, and this work deserves patience.

11. You’ve performed your poetry hundreds of times across the country, but this film captures something quieter and more reflective. What does cinema allow you to do with poetry that live performance does not?

Cinema allows for layering: silence, imagery, memory, and spacing. Film is an inherently intimate form. My writing is very visual, and there is a richness in creating poems that stand on their own and then remixing them for film audiences. It also creates new on-ramps, making the work more accessible and inviting people into the broader catalogue.

12. Finally, what do you hope audiences, especially younger artists and writers, take away from In Need of Seawater as they reflect on their own beginnings and creative impulses?

We are in a moment where many artists are revisiting and honoring the works that first shaped them. I wanted to be part of that conversation. My public identity has evolved significantly through leadership and economic development, and this film is a re-centering of my creative roots. Every artist, whether they remain in the field or not, should honor that part of themselves.

In Need of Seawater is currently available to watch at www.markanthonythomas.com/seawater.