Set in the raw northern mountains of Ras Al Khaimah, far from the familiar image of the UAE, the film reflects Al Khaja’s ongoing commitment to telling stories that resist simplification. Drawing from her own lived experience with tinnitus, and confronting taboos surrounding grief, divorce, and emotional repression, BAAB explores what lingers when silence is inherited and mourning is denied space.

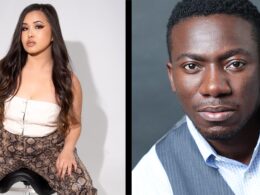

In this interview with IndieWrap, the first female director from the UAE reflects on sound as narrative, atmosphere as language, and the courage it takes to confront discomfort — both personal and cultural. From collaborating with A.R. Rahman to trusting stillness over explanation, Al Khaja discusses how BAAB marked a turning point in her artistic voice, and why some doors must be opened even when what lies beyond remains uncertain.

BAAB takes us inside the fractured psyche of a woman navigating grief through sound, myth, and memory. At what moment did this story stop being an idea and become something you felt you needed to make?

There was a moment when grief stopped being something I was carrying quietly and became something that demanded form. BAAB became necessary when I realised that what I was experiencing could not be explained through dialogue or logic. It needed sound, silence, and space. At that point, it stopped being an idea and became an obligation to myself as an artist.

Grief in BAAB is not linear; it moves through emotional states that overlap, repeat, and distort reality. Why was it important for you to reject a conventional structure and embrace something more fragmented and sensory?

Grief does not move forward politely. It circles, it interrupts, it distorts time. I rejected a linear structure because it would have been dishonest. I wanted the audience to feel disoriented, suspended, and pulled inward, the same way grief behaves. Fragmentation felt closer to the truth than resolution.

Sound plays an unusually intimate role in the film, especially through the presence of tinnitus. How did translating a deeply personal physical condition into a cinematic language shape the way you directed both performance and atmosphere?

Tinnitus is intimate, invasive, and invisible. Translating it cinematically meant directing from the inside out. Performances were guided by what the character could not escape rather than what she expressed. Atmosphere became emotional pressure. Sound was no longer support, it was narrative.

The title BAAB, meaning “door” in Arabic, suggests both passage and threshold. What does this door represent for you, as a filmmaker, a woman, and someone confronting loss?

BAAB, the door, represents transition without certainty. For me, it is the threshold between holding on and letting go, between silence and confrontation. As a woman and a filmmaker, it also represents the courage to step into spaces that are emotionally and culturally uncomfortable.

Arab folklore and myth are woven subtly into the film rather than presented overtly. How did you approach integrating these cultural elements in a way that felt organic rather than illustrative?

Arab folklore lives in tone, rhythm, and intuition, not explanation. I approached it as something felt rather than shown. The myths are embedded in behaviour, space, and sound, allowing the film to breathe culturally without becoming symbolic shorthand.

The northern mountains of Ras Al Khaimah feel like a character in themselves, raw, spiritual, and far removed from the global image of the UAE. What did shooting in this landscape unlock creatively for you?

The mountains of Ras Al Khaimah stripped everything away. There was nowhere to hide, visually or emotionally. That rawness unlocked a sense of spiritual isolation that mirrored the character’s inner world. It gave the film gravity and humility.

As the first female director from the UAE, you’ve often spoken about responsibility, not as a burden, but as a position of honesty. How do you balance deeply personal storytelling with the weight of cultural representation?

I don’t carry responsibility as representation, but as honesty. I tell the story I know intimately and trust that truth travels. Balancing the personal with the cultural means refusing to simplify either. Authenticity does that work for you.

BAAB confronts themes often considered taboo in Gulf societies, including divorce, suicide, inherited silence, and emotional repression. Did you ever feel resistance, internal or external, while developing the film, and how did you push through it?

Resistance exists, especially when silence is inherited. I felt it internally before I ever felt it externally. I pushed through by reminding myself that discomfort often signals something necessary. The film does not provoke for shock, it confronts because avoidance is part of the problem.

Collaborating with A.R. Rahman resulted in a score where music and sound design feel inseparable from the character’s inner world. What surprised you most about working so closely with a composer at this emotional depth?

What surprised me most was A.R. Rahman’s willingness to sit inside silence. The score listens as much as it speaks, and that emotional sensitivity deepened the film rather than overwhelming it.

Visually, the film carries a strong sense of atmosphere and suspended tension, something Abbas Kiarostami once identified as a strength in your work. How consciously do you think about mood as narrative when directing?

Mood is narrative for me. Atmosphere carries information before words do. I think of tension as a language, one that allows the audience to participate emotionally rather than observe passively. That awareness is always conscious in my directing.

Your previous feature Three emerged during the chaos of the pandemic, while BAAB feels more inward, elemental, and personal. How do you see your evolution as a filmmaker between these two films?

Three was about survival during chaos. BAAB is about surrender within stillness. Between the two, I learned to trust quiet, to let absence speak. I became less concerned with explaining and more committed to feeling.

After BAAB, having found what you’ve described as your own cinematic language, what kinds of doors are you now curious, or brave enough, to open next?

After BAAB, I am curious about stories that sit between reality and ritual, where psychology and myth coexist. The doors I want to open next are quieter, darker, and more fearless, both creatively and personally.