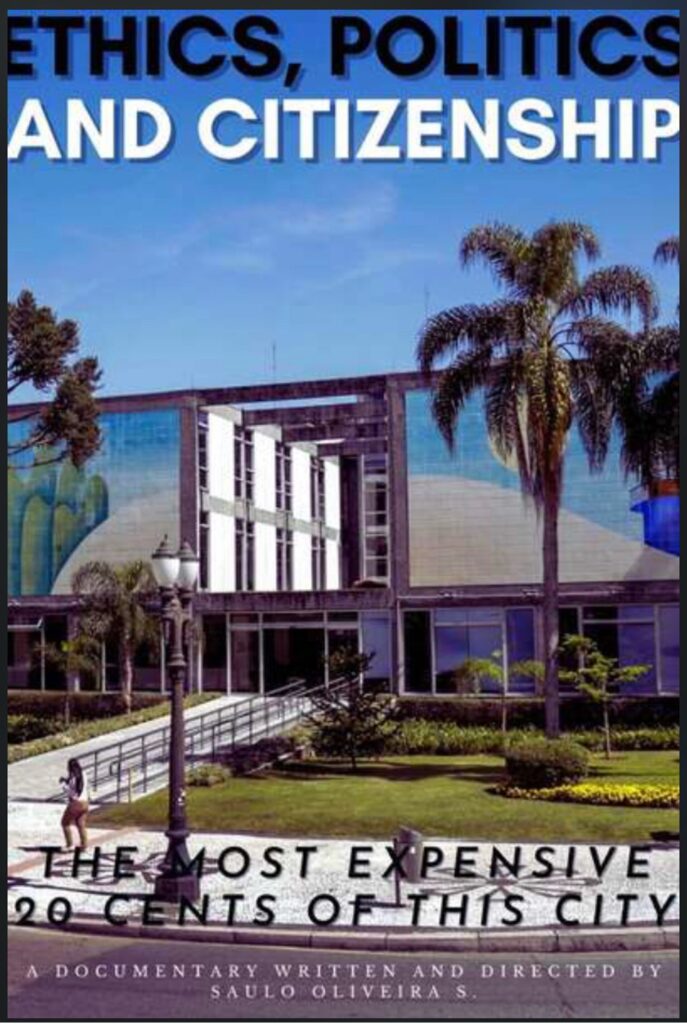

Ever since Saulo Oliveira S., the driving force behind the short documentary Ethics, Politics and Citizenship (directed and scored by him in 2013), first put his name on something related to entertainment, his journey into this fascinating world was officially sealed. In other words, he got bitten by the bug.

The documentary succeeds in following most of the rules of a very interesting technique called Dogme 95. This technique, founded in 1995 by Lars Von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, requires the filmmaker to adhere to a set of rules in order to deliver a movie grounded in reality and authenticity.

The short film is shot on location, avoiding using sets and artificial environments, which is one of Dogme’s characteristics. The film also has all of its shots taken with handheld cameras, portraying a more dynamic and realistic style. Finally, the absence of special effects and post-production modifications sets the tone for the atmosphere that the whole project gravitates towards the most.

There’s also the use of natural lighting, which is an incredible highlight of the film, by the way, with the silhouette of Curitiba City, Brazil, being filmed at a beautiful sunset. The last rule, thou, Saulo didn’t adhere to. Nevertheless, the lack of this last rule is far from being a downfall in this regard. There is music there, a sound not recorded in location, as one of the rules of the Dogme says, but composed by Oliveira, which makes everything even brilliant.

The film explores the intersections of ethics, politics, and citizenship, not as academic abstractions, but as urgent and lived experiences. Through a reflective, non-linear narrative, it challenges the viewer to rethink personal responsibility within societal structures, making the viewer both subject and object of critique.

When it comes to its style and cinematic approach, the film embraces an experimental, almost poetic visual language. Unconventional camera angles—ranging from intimate close-ups to skewed perspectives—recall the visual syntax of Chris Marker (La Jetée), infusing static imagery with layered weight. The subdued color palette enhances the film’s contemplative tone.

When it comes to the rhythm and narrative cadence, Saulo Oliveira’s direction is precise. The film’s pacing is deliberately slow and occasionally disorienting, reminiscent of Alain Resnais or Godard’s essayistic works. This fragmented flow mirrors the thematic ambiguity, refusing easy answers and inviting intellectual engagement.

As said, the original score, composed by Oliveira himself, is a highlight. A blend of minimalist piano, ambient noise, and electronic textures weaves a sonic fabric that deepens the film’s emotional landscape. The synergy between sound and image elevates the viewing experience, reminiscent of Sans Soleil (1983).

Despite its conceptual density, the film carries strong emotional undercurrents. Juxtaposed visuals and sparse yet powerful text confront the viewer with the ethical numbness and political alienation of modern life. It doesn’t seek to instruct, but rather to awaken.

In terms of reflective impact and social relevance, although Saulo declared in an interview years after the film that he does not agree with the conservative bias that follows from the ideology of the lawyers interviewed, it is still sticking and current that scene in which young people, imbued with the rebellion of the June Journeys, decide to camp in front of the city hall.

In a way there is reason in the concern of the most conservative lawyers, that is, the inclination for change that moves youth, despite always welcome, contrasts with the very lack of wisdom of young people on how to channel this spirit in the best way to achieve a practical result valid for the community. The Black Blocs of the 2013 of plenty demonstrations in Brazil on Ethics, Politics and Citizenship are an example of this.

In this sense, in terms of intertextuality, the film is brilliant. The protesting scene in front of the city hall, a few meters from where the attorney general of the municipality was interviewed, brings to reflection the inescapable subjectivity of the opening phrase of the film that quotes Immanuel Kant. After all, if each one acts in a way to become a standard of conduct, isn’t one still distancing oneself from some common point of ethical or citizen behavior? Will there be a consensus? This is one of the greatest triumphs of the film: reflection.

After all these years, Ethics, Politics and Citizenship stands as a bold, thoughtful piece of experimental cinema. It’s endeavored with its soul, plunged in the mood of Saulo’s notorious dark academia texture of approach. Short, indeed, but vast in its thoughtful exercise, it provokes more than it resolves—and therein lies its value.

Simply put, rooted in some avant-garde tradition, the short film echoes the modus operandi of Michael Snow’s Wavelength or Harun Farocki’s cinematic essays. It disrupts narrative expectations, using form as an extension of meaning, art as an intellectual and political act.

Speaking of political acts, that’s probably one of the last of Saulo’s testimony on his early days of activism.

After moving thousands of people who signed his petition to curb a scene of racism in a reality show, after demanding in his song What Governs Behind Them? “Free the working class hero man, give him the Nobel” – a protest for the freedom of the then imprisoned Luís Inácio Lula da Silva -, after protesting for world peace, refusing not to cut his hair until the world reached it (which lasted a year and a half and yielded beautiful images of the long-haired model), a la John Lennon while holding a sign that said “War is Over”, after claiming more protection for the Amazon Forest (participating in the #defundbolsonaro movement), finally, after all the most notorious acts of his idealistic and activist profile the short film remains as a portrait of a time in which a naive-rebel Saulo observed other rebellious spirits. The making of this movie underlies the motivation of the activist impulse that, until 2022, Saulo himself cultivated in his trajectory.

But after all this, what is left when the spirit of a motivating political activism vanishes? If you are Saulo Oliveira, creativity will still be there, above all, always driving you towards something increasingly stimulating. He might no longer believe in world peace or saving the environment, but the vein of entertainment did not let him.

And, if the insect bit him hard enough, it is clear that Oliveira could not help but try a new form of narrative and a new theme.

Being creatively restless made Saulo conceive Oyster, a limited television series concept that gained high praise at the Sir Peter Ustinov Television Scriptwriting Award from the International Academy of Television Arts & Sciences – Emmy -in 2022 and was highly esteemed at the BAFTA Rocliffe New Writing Competition – TV Drama in 2023.

Even though they are awards parallel to the main Emmy and the main BAFTA, guiding and honoring writers to perfect their craft, Oliveira’s willingness to participate in them marked the opening of the creator to the eyes of specialized critics and in taking part in future award circuits. By debuting in the Emmy and BAFTA terrain, Saulo Oliveira S. gave the green light to external creative intervention in the project, with potential partnerships to get Oyster off the paper.

The story follows Kristopher Kingsley, father, husband, and, as an actor, which is more, a staunch adept of Stanislavsky’s method. The moment he plunges his persona into the mind of an 80’s reckless rockstar that he has been hired to portray in a biopic (Oliver Oyster), he faces mental instability. He doesn’t know who he is, doesn’t recognize his daughter and even denies the existence of his dying mother. The embodiment and personification of this criminal rock legend will raise scandals, wars of egos, betrayals, alliances and revelations on Oyster backstage.

Oyster masterfully weaves past and present, performance and reality, creating a labyrinthine narrative that echoes meta-fiction and psychological drama. The pilot has a strong inciting mystery—who is Kristopher really?—and builds emotional and narrative tension through fragments that blur actor and character. The pacing is bold: slow-burning at first, with dramatic spikes (the egg attack, school bullying, therapist scene) that feel both shocking and meaningful.

And, considering that after a fight with his wife that followed her disappearance for weeks, the rockstar Oliver Oyster was sentenced to the death penalty when it came to light what he had done, the first episode ends with a strong cliffhanger since, after Kristopher fights with his wife, she is also missing for weeks, and now investigators knock on the actor’s door wondering if the line between genius and insanity has been crossed by the multi awarded Kris King in this immersion of troubled preparation.

Kristopher Kingsley is richly drawn: a celebrated, fractured figure caught between multiple selves—father, son, actor, rockstar. His psychological unravelling is central, channelling characters from Black Swan or Synecdoche, New York.

While the play between reality and role (Kristopher vs. Oyster) remains a standout, there’s a recurring question: Is he acting or becoming? – The commentary on celebrity, the consequences of pursuing excellence and trauma is handled with both subtlety and explicitness.

In general, Oyster is daring, self-aware, and rich in allegory. It plays with memory and ego with confidence. It is a story about the collapse of self in the name of achieving perfection, infused with visual and narrative substance. With minor refinements, the author says he needs to do in dialogue rhythm, it has the potential to stand beside series like Succession, The Undoing, or the recent The Studio in ambition and originality.

Meanwhile, the answer to whether Oliveira’s return to entertainment is expected only to release an album at the end of the year or if he will also return to continue the miniseries project is as enigmatic as he is.

After the good outcome from taking part in the circuits, by expanding networking and collecting praises from critics and insiders for the brilliant premise of the miniseries,

Oliveira is willing to talk and negotiate the advancement of the idea with industry professionals, but no news can yet be confirmed about the second act in this plot.

In conclusion, since he always has attractive ideas that raise good discussions, Saulo Oliveira’s next steps are worth attention because, between one act and another in this trajectory, the next masterpiece might be just around the corner.