We’re so happy to have you with us today! To start, could you each introduce yourselves and tell our readers a little about your background and what led you into filmmaking?

David : I was born in Afghanistan and never really stopped moving from place to place. The allure of travel, cultures, and the stories that bind have always intrigued me from a young age. Growing up as a traveling expat, I only had access to a small number of things that connected me to my American heritage. Movies became a huge part of that connection. After obtaining a degree in communication, media and film, it became clear that I needed to pursue filmmaking and learn how to craft compelling stories of my own. So, I moved to Los Angeles and the rest, as they say, is history.

Sarah : My passion for storytelling began in high school theater and led me to earn a bachelor of arts in theater. After beginning my career as a film and stage actress, my creative path shifted when I devoted myself to raising seven children who joined our family through adoption. Writing became my primary artistic outlet. When I read Izidor’s autobiography in 2014, I immediately saw the cinematic potential in his story and felt a deep calling to help bring it to the screen. This project has been a meaningful convergence of my creative background, personal experiences, and love of redemptive storytelling—and a way to reconnect with the artistic path I’ve always felt drawn to.

David and Sarah, can you each share what first drew you to Izidor’s story and why you felt compelled to tell it through film?

David : A mutual friend introduced me to Izidor and Sarah in the summer of 2015. We met at a coffee shop on Main Street in Santa Monica and ended up talking for hours. I was immediately captivated by Izidor’s story. I read his biography, explored every piece of media coverage I could find, and immersed myself in the political history of Romania, particularly as it related to the treatment of orphaned children.

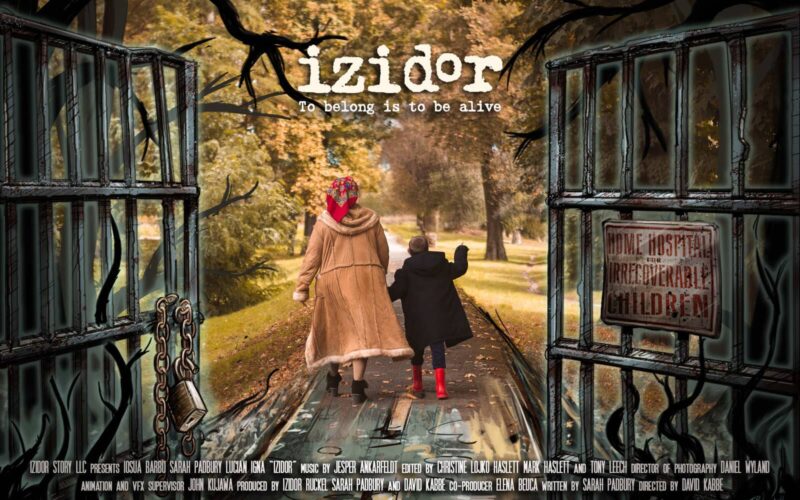

But there was one moment in his story I couldn’t shake: the day a nanny took him outside for the very first time. That image stayed with me. Over the course of a few years, our friendship grew and the story began to solidify in my mind. Eventually, it wasn’t just an idea I admired; it became a story I had to tell. I’m a filmmaker. There was no other option.

Sarah : As an adoptive parent, I’ve seen firsthand how deeply misunderstood adoptees and so-called “orphans” can be in our culture. This is especially evident in films, where the orphan trope often downplays the lasting impact of trauma or, worse, turns the child into a villain. These portrayals reinforce harmful stereotypes and fuel misconceptions about real people—our neighbors, our children. With this film, I set out to tell a more honest story—one that reflects the true experience of a vulnerable child and points to where lasting hope and healing can really be found.

Sarah, as an adoptive mother of seven and a child advocate, how did your personal journey influence the storytelling in IZIDOR?

Sarah : In both life and film, people are naturally curious about someone’s “origin story.” Over the years, I’ve often faced insensitive or hurtful questions about my family—sometimes asked right in front of my children—questions no one would think to ask about biological children. I’ve had to learn how to respond with grace, using those moments to gently educate others about respectful adoption etiquette. Parenting children from hard places brings a unique learning curve, and it requires a lifelong commitment from parents to be willing to look at their own histories and adapt in ways that may not look typical, but are profoundly necessary. I’m still learning!

When Izidor shared how the real Onisa treated him, it struck me deeply—it was as if she instinctively knew and practiced the very principles that I’ve spent years trying to absorb. In writing IZIDOR, I wanted to portray that kind of authentic, compassionate action—what it truly looks like to step into a vulnerable child’s world and make a difference.

David, your career spans from documenting wars to now making your narrative debut with IZIDOR. How did your previous work shape your approach to this project?

David : I’m still stunned by how deeply evil human beings can be. Covering genocide and war crimes is a mind-bending experience. It forces you to confront the staggering capacity for cruelty, especially when it’s carried out under the banner of government policy or war. The scale of atrocity can be overwhelming.

For me, the only way to keep going has been to focus on the good and seek out the diamonds in the rough. That practice has not only helped protect my mental health, but it’s also led me to some of the most beautiful and courageous people I’ve ever met. As G.K. Chesterton wrote, “Any dead thing can go downstream, it takes a living thing to go up it.”

Witnessing the depths of human suffering has strangely equipped me to see, and truly believe in, the power of hope. Without those experiences, I’m not sure I would have grasped just how real and transformative hope can be. I’m still learning. And making this film has shown me that I’ve only just begun to understand it.

IZIDOR uses both animation and live action in a unique way. What inspired you to depict the orphanage in animation and the outside world in live action?

Sarah : We faced the difficult task of portraying a world that was truly dark and terrifying. Under communist rule, tens of thousands of disabled children in Romania were warehoused in “home hospitals”—places more accurately described as asylums. The abuse they endured was too graphic to depict in live action, so we made careful, high-stakes decisions about how to convey these realities with integrity and compassion.

Animation became our solution. It allowed us to depict life inside the asylum with sensitivity, while still capturing its emotional and psychological brutality. Animation Supervisor John Kujawa (South Park) crafted a deliberately unsettling environment designed to make viewers feel the same urgency to escape that Izidor felt. We chose a color palette centered on Pantone 448 C—a shade dubbed the “ugliest color in the world” by psychological researchers—to evoke discomfort. In addition, the characters move in ways that are not-quite human, the children’s faces are blurred though their voices are always present, and the backgrounds precisely mirror the real building’s architecture, linking the animated and live-action worlds. Every element was carefully crafted to draw the viewer into Izidor’s perspective, amplifying the tension and emotional impact.

On the live action side, our incredible Romanian crew—DP Daniel Wyland, 2nd Unit DP Stefan Aghitoaie, Drone Pilot Paul Plesha, and Sound Technician Daniel Rizea—helped fulfill (director) Dave’s vision to make the real world beyond the asylum exceedingly beautiful, magical and full of light.

This visual contrast between the grim animation and the live action reinforces the story’s core: the power of belonging and hope break through even the darkest places.

Filming in Izidor’s actual hometown must have been emotional. What was the most powerful or challenging moment on location in Romania?

David : It was when the cameras weren’t rolling. When the lights weren’t on. Just being in the asylum with Izidor and witnessing his courage to go back there to the place of his trauma and have the generosity to bring us into his life in such a beautiful way. That’s all I will say about that.

Sarah : We needed to create an authentic setting for Onisa’s home—set in 1980s communist Romania—and had just three weeks on location to find, dress, and shoot it. After sharing reference photos of the interior we envisioned, a local community member led us to an unoccupied, unrenovated house that perfectly fit the period.

With the help of dedicated volunteers, we transformed the space into Onisa’s home. A group of local women took the lead, bringing out cherished family heirlooms and traditional textiles to ensure every detail felt true to the era. Their contributions were so spot-on that several Romanian crew members exclaimed, “I feel like I’m in my grandma’s house!”

Watching the house evolve—from cobwebs and dust to a warm, lived-in home—was a powerful testament to the spirit of community. The Romanian crew lit and filmed the family dinner scene with great care, capturing its warmth and intimacy. Director Dave worked patiently with the child actors, creating an environment full of encouragement and trust. Together, these efforts made it one of the most awe-inspiring moments of the entire shoot.

Sarah, portraying Onisa — the courageous nanny — must have been intense. How did you prepare to step into her shoes, both emotionally and as a first-time lead actress?

Sarah : Because I’ve been researching Izidor’s story for nine years, I feel a deep connection to the real Onisa. Although I never had the privilege of meeting her on this side of heaven, I’ve spent time with her family, pored over countless photos, and listened to many stories about her fierce love for the children locked away in the hospital. That emotional foundation gave me a strong starting point to step into her shoes.

As this was my first time leading a film as an actress, I approached the role with both reverence and intention. I spent time imagining Onisa’s daily life under the weight of communist Romania—the quiet resistance, the moral choices, the constant risk. To physically ground myself in her world, I practiced Romanian speech patterns and observed how women of her generation carried themselves.

Emotionally, I leaned on empathy. I’m a mother who has spent years parenting children from hard places, so the protective, nurturing instinct that Onisa embodied wasn’t foreign to me. But I also had to tap into her extraordinary courage—choosing to act when it was dangerous, lonely, and uncertain.

It was an honor to portray a real woman who quietly defied a brutal system to give one child a glimpse of belonging and dignity. I took that responsibility to heart, and I hope she would feel seen and well-represented in this film.

David, you’ve mentioned that “sometimes the best stories find you.” How did telling Izidor’s story differ from the other humanitarian stories you’ve documented around the world?

Izidor and Sarah found me. I just kept saying yes. One yes led to another, and over time, those small steps brought me to this project.

In war zones, stories come at you fast and unfiltered. It’s like drinking from a firehose and hoping it’s water. You’re often reacting in real time, trying to capture truth as it unfolds under extreme circumstances. With IZIDOR, the process was very different. I had the rare opportunity to slow down, to deeply research one powerful moment in his life and carefully build the world around it. That depth and focus made the storytelling process more intentional and layered.

That said, the emotional weight is similar. Whether you’re in a conflict zone or digging into personal trauma, it’s always an emotional rollercoaster. But with IZIDOR, that journey led to something uniquely intimate and redemptive.

You attracted an impressive crew despite being a low-budget short film. What do you think made seasoned professionals want to join the IZIDOR project?

David : Our dominant strengths were having an extraordinary coming-of-age story and Sarah’s solid screenplay revealing a powerful way to tell it. We also had a strong grasp of the subject matter, a firm belief this film could help vulnerable children, and a commitment to make a high-quality film if we could convince top-notch artists and crew members to join us. But most importantly, we had Izidor Ruckel’s trust that our proposed film would represent him well.

The screenplay opened the door for conversations with talented artists and crew. The next hook was our distinctive use of animation and live-action. This was a fun way to start a conversation about cinematic history and how directors use new techniques to disrupt the status quo. I shared my vision for how the film would take a fresh, innovative approach to storytelling—flipping familiar film tropes on their heads and generating excitement for something truly original. Along the way, we discovered many people yearning to put their fingerprints on a film bound to do good in this world.

In the end, we are so grateful for the incredible folks took a leap of faith and trusted us with their time, talents, and efforts:

· Danish Composer Jesper Ankarfeldt (Straatcoaches vs Aliens; Love, Lies and Alibis; Houvast)

· Animation Supervisor John Kujawa (South Park)

· Editors Christine Haslett (How to Train Your Dragon, Trolls) and Mark Haslett (Last House on the Left, Let’s go Luna!)

· Animation Editor, Online Editor and Colorist Tony Leech (Escape from Planet Earth, Hoodwinked!)

· French Sound Designer Ben Jacquier (Battle Royal Ultimate, The Last of Us, Space Agents)

· Sound Mixer Dom Camardella (Grammy-winning audio engineer)

What message do you hope audiences will take away after watching IZIDOR?

David : This film isn’t just about an orphan; it’s about an adult having the courage to return to the deepest depths of trauma and find peace. From that perspective, IZIDOR becomes universally relatable. At some point, we all must confront the child within us. And if Izidor can face that pain and come through it, so can you.

For those who have already walked that path of healing, the film offers another invitation: to be like Onisa. To go into the world and carry out acts of courageous kindness that can change someone’s life.

At its core, this film is a deconstruction of hope, stripped down, examined, and rebuilt. By the end, we offer the audience a chance to reconstruct hope for themselves, on their own terms.

My greatest hope is that it inspires healing—in yourself, and in the lives you touch.

If you could describe IZIDOR in just three words, what would they be?

David : Izidor the person: Brave, Introverted, Generous

IZIDOR the film: Raw, Real, Moving

Sarah : Izidro the person: Compassionate, Transformed, Hopeful

IZIDOR the film: Powerful, Truthful, Hopeful

Favorite moment on set — a memory you’ll carry with you forever?

David : The film needed a bit of levity, so we added a light-hearted joke in the dinner scene about a frog. But there was a problem: Izidor had never been outside before and therefore wouldn’t realistically know what a frog was. That meant we had to show him encountering one during his day outdoors.

Every night in Romania, I could hear frogs everywhere, and the crew kept assuring me they were all around us. But when we went looking, we couldn’t find a single one. Without the frog, the joke wouldn’t work.

On our final day of shooting with the outdoor sequences, we were heading up the mountain to capture the sunset shot, and I was feeling pretty defeated about the frog. Then, out of nowhere, the production vehicle hit a pothole with a loud thud, and I thought the axle might’ve broken. Our DP, Daniel Wyland, and I got out to inspect it—and there it was. Sitting in a puddle in the pothole was our beautiful, perfect frog! It was a little miracle. The joke was saved, the vehicle was fine, and everything worked out.

That moment was just one of many small, serendipitous wins on this shoot—reminders that sometimes the story shows up exactly when you need it.

Sarah : The final scene we shot between Onisa and Izidor was also their last moment together in the film—a powerful culmination that the entire story had been building toward. It demanded deep emotional vulnerability from Iosua Barbu, the eight-year-old Romanian actor playing Izidor. When it came time to film his close-up, we needed real tears—and he delivered with stunning authenticity. I remember watching the monitor, jaw dropped, as this first-time child actor gave a pitch-perfect performance. Dave yelled, “Cut!” and we exchanged a high-five, declaring, “We have a film!” In that moment, I knew without a doubt that audiences would be moved—not just by the story, but by the raw humanity shining through this young boy’s eyes.

What’s next for each of you? Are there new projects in development that continue this focus on human rights and storytelling?

David : In development, I have an anthology series, a Western set in the Pacific Northwest, and a limited series about the first undercover journalistic investigation in history. I’m also continuing to help develop the IZIDOR limited series.

Sarah : The short film IZIDOR is drawn from a limited series I’ve written, based on Izidor Ruckel’s full life story. I’m currently seeking partners to bring this story to life on location in Romania. Set in the 1990s in both Romania and San Diego, the series explores what happened to 10-year-old Izidor and his friends during the collapse of Communism—some rescued through adoption, others left behind. It also highlights the unsung heroes who risked everything to help these children escape and begin the difficult process of healing.